Have you ever…

…struggled to maintain healthy relationships or let go of unhealthy ones?

…unable to feel happy or fulfilled regardless of how successful you are?

…cared a lot about how other people see or think about you?

If you answered yes to any or all of the above questions, then you most likely had experienced shame or made attempts to avoid feeling it.

So what is shame and why does naming it evoke such strong feelings of confusion, fear, and dread in us? Before I answer the first question in depth, let me address the second question first.

There is an unspoken rule in polite society about shame: We don’t talk about it.

This is because shame compounds on itself (ie. there is shame about feeling ashamed). Talking or thinking about it inevitably brings up more shame in the forms of painful feelings, thoughts, and memories that we would rather forget or not know about. Therefore, our social and personal aversion to shame is understandable.

However, avoiding or ignoring shame doesn’t make it go away or lessen its negative impact on our lives or society. In fact, avoidance only increases and worsens the feeling of shame.

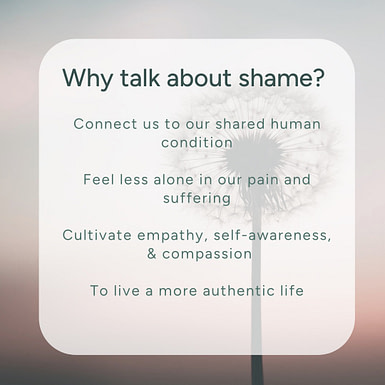

That’s why we need to break this code of silence and talk about shame, so we know that we’re not alone in our experiences.

Let’s de-shame shame.

What is Shame?

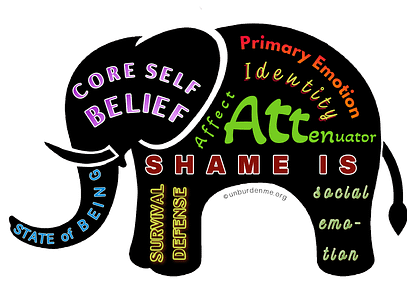

According to Tomkins’ Affect Theory, shame is one of the nine primary innate affects that are “hard-wired, preprogrammed, genetically transmitted mechanisms that exist in each of us and are responsible for the earliest form of emotional life.”

2 Positives: Interest-excitement, enjoyment-joy

1 Neutral: Surprise-startle

6 Negatives: fear-terror, distress-anguish, anger-rage, dissmell, disgust, shame-humiliation

Together, these affects form the core system of human motivation and serve important roles in our physical survival and emotional health.

Therefore, the shame affect is a natural part of our biological inheritance, not a flaw. Everyone experiences shame or is vulnerable to feeling shame. It could be from a mildly embarrassing situation of saying “Hi” to someone but they don’t recognize us to an intensely painful experience of being abused, neglected, or abandoned by a loved one.

We all have it, which leads me to the First Principle of Shame:

Shame is a normal universal human experience

What’s the purpose of shame and how does it work?

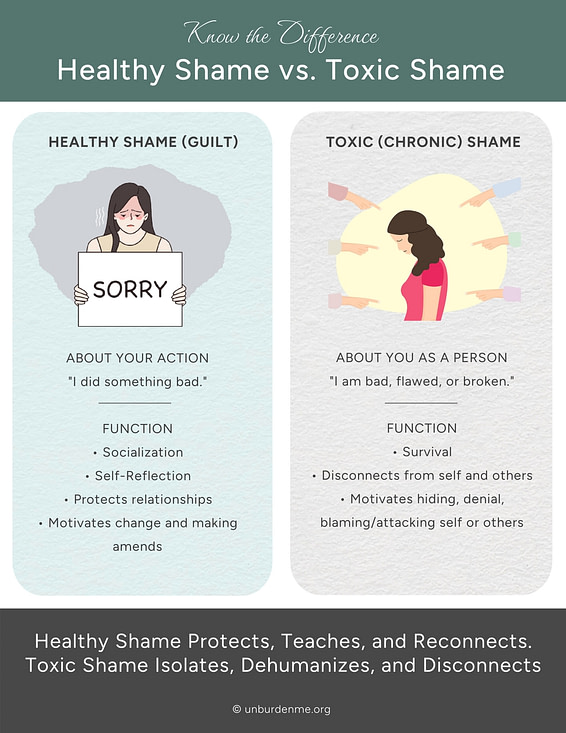

Although shame is a normal universal human experience, it’s certainly not a pleasant one. In fact, shame is usually described as an intensely painful emotional experience with a negative core self-belief that one is inherently flawed and unworthy. But just like we need some salt in our diet, shame is a necessary part of human life in small doses.

To really appreciate the role that shame plays in our lives, we need to understand how it works.

Besides being a primary affect, shame also acts as an affect attenuator for the positive affects (Interest-excitement, enjoyment-joy), similar to tapping on the brake of a car. The good feelings get reduced but they do not stop completely: you shoot but don’t score; you apply for a job but don’t get it; you’re excited about an idea but your family or partner doesn’t share in your enthusiasm. This is why shame is sometimes referred to as a social emotion since it usually gets triggered in interpersonal and social situations. How much shame gets personalized and internalized into a negative self-concept depends on the individual’s coping skills, inner resources, and their external support system.

"Shame is the sudden interruption of pleasure." Tompkins

In effect, a healthy amount of shame, like a good car brake, helps us define the limits and boundaries of our positive pursuits and keeps us from driving off the cliff. It tells us when to pause, slow down, watch where we’re going, scan for danger, or make a correction if needed before proceeding. The interruption of pleasure brings our attention to the problem or potential problem so we can deal with it before our excitement takes us over.

With that in mind, here are 3 main purposes of shame:

- Survival Defense - Protect us from getting ostracized from the tribe or family when we misbehaved, especially when we’re young and helpless.

- Socialization - Helps us fit in by adapting to social norms and navigating the world to get our needs met within limits.

- Self-reflection - Motivate learning and growth by changing our attitudes and behaviors when we fail to live up to our own values or standards.

In short, the appropriate use of shame in the above context is healthy. However, when shame is used as a tool to humiliate, oppressed, and punished excessively without any explanation or repair, it can turn into pervasive toxic shame.

Healthy Shame/Guilt vs Toxic Shame

As John Bradshaw noted, “What I discovered was that shame as a healthy human emotion can be transformed into shame as a state of being. As a state of being shame takes over one’s whole identity. To have shame as an identity is to believe that one’s being is flawed, that one is defective as a human being. Once shame is transformed into an identity, it becomes toxic and dehumanizing.”

We can see how these two types of shame can develop in the following example:

A little girl runs out into the street to chase an ice cream truck without seeing a car turning the corner. Her mother sees this through the front window and shrieks loudly, “No! Stop!” This startles the girl and she freezes in the middle of the street as her mom runs out to grab her. Once they are safely back inside the house, the girl breaks down and cries uncontrollably. There are 2 ways the mother can handle this:

- She can comfort her daughter and explains what happened: “Are you ok? Are you hurt? You’re safe now but what you did was not ok. You could’ve been hurt and I yelled because I was really scared that the car would hit you. Next time ask me to come with you if you want to get some ice cream. It’s not safe for you to run out into the street like that by yourself. Do you understand what I’m saying?” OR

- She can discipline her daughter by screaming at her: “What’s wrong with you? Why did you do such a stupid thing?! You could’ve been killed! Don’t you dare leave the house again without me! No more ice cream for you! Now go to your room and think about what you did!”

In the first approach, there is a clear display of warmth, concern, and care as the mother explains what happened. She focuses on her daughter’s behavior, why it wasn’t ok, and what she wants her daughter to do differently next time. This turns an acute shaming experience into healthy shame or guilt with a lesson about street safety without damaging the mother-daughter relationship or the daughter’s sense of self.

While the second approach is understandable after the shock they just went through, the little girl most likely will not hear her mother’s concern or fear through those harsh words. Instead, she will feel more shame, thinking that she’s bad and that her mother hates her. The excitement, delight, and joy she has about ice cream were cruelly squashed and replaced by negative feelings of shame. This may set her up to have a contentious relationship with her mother and sow the seed for toxic shame that can manifest later as self-destructive behaviors.

How to identify shame?

There are usually 2 main reactions when people hear the word “shame”:

- Overt Shame (All pervasive) - Hyperaware of it and don’t want to talk about it.

- Covert Shame (Bypassed) - Unaware or unsure of having or ever experiencing it. May believe that shame is something that happens to other people, not them.

Neither reaction is correct, good, or better than the other. It just makes shame trickier to identify and work with when everyone has such a different level of awareness and reaction to it. Here are a few examples for each group:

Overt Shame

- Get anxious and fearful about making a mistake or being criticized

- Have a loud inner voice that tells you “You’re bad or not good enough.”

- Arrange your life around avoiding people, places, things, or events that can trigger shame

Covert Shame

- Have a sudden strong reaction (angry, yelling, blaming) to something or someone and not sure why.

- Feel confused about why you suddenly quit a project/class/job, leave a relationship, or pick a fight with your partner when things are going well.

- Have a hard time discerning if you were abused, neglected, mistreated, or manipulated.

Which group do you identify with? Maybe a little bit from both?

That is not uncommon. We all have shame-sensitive areas that we’re hyper-aware of and other areas where shame is more subtle, hidden, and invisible from our awareness. This is because shame is designed to protect us by hiding behind other experiences (ie. being prideful, attacking or blaming others), and binding to other feelings (anger, grief, joy) to keep us safe from physical harm, emotional pain, or relational loss (real or perceived). Nevertheless, it’s important to have an awareness of our own unique “map of shame,” where we have overt or covert shame, so we can deal with our feelings and reactions to shame with more clarity, compassion, and understanding.

What happens to the body when we feel shame?

Shame is experienced as more than just a feeling. It’s an entire organismic state that affects multiple systems in the body at once. When triggered, our entire body automatically goes into shame whether we want to or not.

Here are some common indicators of shame that you might recognize or have experienced:

Physiology Indicators:

- The impulse to cover up and hide

- Head lowered, neck and shoulders slump and pull in

- Eyes look down, away, closed, or hidden to avert direct gaze

- Upper body curved in on itself as if trying to be as small as possible

- Arms and/or legs may be crossed, like in a fetal position

- Slowed or fragmented thought and speech: going blank, can’t think, getting confused and tongue-tied

- Acute state (Hyperarousal) - Blushing, sweating, and increased heart rate

- Chronic state (Hypoarousal) - Collapsed stance, hunched over posture, slow gait, shy demeanor OR puffed out chest, nose, and chin raised up in the air, tense arms, arched back to correct for the collapsed stance.

Thought Indicators:

- “There is something wrong with me.”

- “No one will ever love me.”

- “I hate myself.”

- “I should’ve known better.”

- “I’m bad. I’m toxic.”

- “I don’t want to talk about it.”

- “I’m so stupid.”

- “Why can’t do anything right?”

- “I’m not good enough.”

- “I want to disappear.”

- “Don’t look at me.”

Feeling Indicators:

- Disrespected

- Exposed/Vulnerable

- Attacked/Insulted

- Hurt

- Small

- Weak/Inadequate

- Worthless

- Powerless

- Judged

- Self-Conscious

- Like “shit”

Behavioral Indicators:

- Attack or blame others

- Deny, deflect, or avoid the topic or person

- Numbing out or distract with activities (video games, shopping, sex, alcohol, drugs, food, exercise, work)

- Suddenly become mute and forget your thoughts or words

- Attack yourself with negative self-talk

- Physically withdraw, pull in, or run away

- Cling harder to other people to feel safe

- Collapse in despair and helplessness

Now that we have a clearer picture of what the experience of shame looks like and feels like, let’s take a look at what causes it in Part 2.