As we learned in Part 1, shame is an inherent aspect of our genetic makeup as human beings. Therefore, there is no particular “cause” of shame since it is an innate affect that we were born with, much like joy or excitement. However, the way shame gets triggered, expressed, and managed is heavily influenced by our environment and life experiences. For example, how the community or culture perceives and treats mental health issues can exacerbate or diminish the impact of shame on individuals experiencing them.

In general, individuals who grew up in stressful and dangerous environments may be more prone to experiencing and internalizing toxic shame as a way to survive and protect themselves. This can occur during times of socialization, following traumatic events, or living in abusive situations.

This leads to the Second Principle of Shame:

Shame develops as a complex survival response during stressful or traumatic events

Socialization

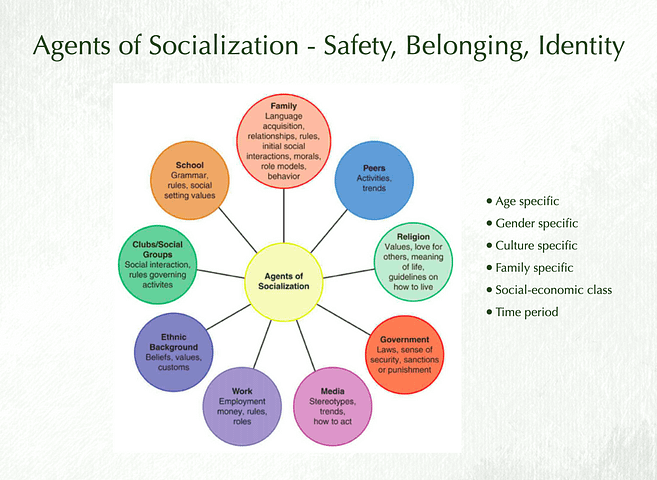

For centuries, various cultures and societies have utilized shame and guilt as means to regulate individuals, maintain social harmony, and foster unity and cooperation within groups. During childhood, we were taught how to conduct ourselves and respond according to the norms, customs, traditions, rules, and values of our family, community, and nation through a system of rewards and punishments. This approach aimed to assist us in maturing into respectable, responsible, and productive members of society.

Over time, a sense of healthy shame or guilt becomes a part of our core beliefs, serving as an inner moral guide or conscience. This helps us fit in and avoid social rejection, by adhering to and acting within the established social norms and values. These rules may be spoken or unspoken as they get passed down through the generations:

- It’s a sin to have sex before marriage

- Always put the family first over your own desires

- Everyone must conform to their prescribed gender role or identity

- Children must obey and respect their parents and the authorities without questions

In addition to our main caregivers, we are also influenced by other socializing factors in our surroundings that continue to shape our values, beliefs, identity, self-worth, and belonging. The impact, positive or negative, depends on the messages we have internalized from these sources.

When these messages are conveyed in a shameful, threatening, conflicting, or inappropriate way, they can have a traumatic effect on a child's socialization process. This can cause them to mature too quickly or struggle to transition into adulthood. The extreme cases of child soldiers in Africa and Hikikomori, a severe form of social withdrawal among Japanese youths, are examples of the negative consequences of problematic socialization.

Trauma-Related Shame

Trauma is an overwhelming event that can leave a lasting harmful effect on a person’s physical, mental, and emotional health which I previously described here and here. Out of all the various forms of trauma, childhood trauma that involves repeated, chronic abuse and/or neglect by caregivers is the biggest contributing factor to the development of toxic shame. This type of trauma is called Developmental Trauma (DT). It is also described as intergenerational trauma, inherited trauma, cultural trauma, attachment trauma, and Complex-PTSD or C-PTSD in adults.

A paper from Front Psychiatry published in 2022 refers to DT as “the complex and pervasive exposure to life-threatening events that

- occurs through sensitive periods of infant and child development,

- disrupts interpersonal attachments,

- compromises an individual's safety and security operations,

- alters foundational capacities for cognitive, behavioral, and emotional control, and

- often contributes to the development of complex PTSD in adulthood.”

What makes the impact of Developmental Trauma so devastating is that the experience violates the fundamental human need to feel safe, loved, and empowered. When childhood trauma disrupts our sense of safety and trust, fear and shame become the dominant driving forces that shape our physiology and neural development, leading the brain to prioritize survival over growth and connection.

According to Janina Fisher, “Shame is a survival response, as crucial for safety as fight, flight, and freeze when submission is the only option."

This is particularly true in developmental trauma. An infant or child who is experiencing abuse and/or neglect is placed into an impossible dilemma when their caretaker is the source of danger. They are unable to defend themselves, escape, hide, or cry for help as it could worsen the abuse. Therefore, the child can only submit and comply in order to minimize further harm and cope with this inescapable terror.

To make matters worse, some caretakers exhibit a dual personality: they act as loving parents when sober but transform into angry tyrants when drunk. This inconsistency can be confusing and upsetting for children, who may struggle to discern what is truly safe and real. The situation leads to a difficult internal struggle for the child, as they try to balance their longing for love and affection with their fear and anger toward their parents. In order to solve this inner conflict, a child may unconsciously associate shame with certain memories, bodily sensations, feelings, or thoughts that they or their caregivers consider unacceptable or dangerous. What was not allowed to know or feel gets blocked or inhibited by shame from their awareness. This allows children to construct a coherent story about their identity and upbringing, without feeling the pain or persistent tension of conflicting emotions that can threaten the relationship with their parents.

For example, a child who was punished or threatened with abandonment for expressing their needs might learn to be quiet, stay invisible/small, suppress their anger, or become a people pleaser. Knowingly or not, they have internalized messages that shame them for having or expressing needs. They might say things like:

“I don’t want to be a burden to anyone.”

“It’s not safe to have needs. People can use that against you.”

“If I tell people what I really want or need they might leave me.”

“If I don’t have any needs, then I won’t be disappointed.”

“It’s better to be quiet and not express myself. I don’t want to upset others.”

“People who have needs are selfish. I should only think about what other people need instead of myself.”

Unfortunately, these thought patterns can become self-defeating in the long term. John Bowlby noticed that children who must disown their traumatic experiences develop serious problems including “chronic distrust of other people, inhibition of curiosity, distrust of their own senses, and the tendency to find everything unreal.”

Shame, in essence, is an adaptive and instinctive survival response that can arise during stressful or traumatic events. Without proper treatment, it can evolve into more problematic behaviors and personality traits that can limit one’s capacity to heal, love, and live a more fulfilling life, which I’ll explore in Part 3.

References

Cruz D, Lichten M, Berg K, George P. Developmental trauma: Conceptual framework, associated risks and comorbidities, and evaluation and treatment. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Jul 22;13:800687. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.800687. PMID: 35935425; PMCID: PMC9352895.

J. Bowlby, A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 103.